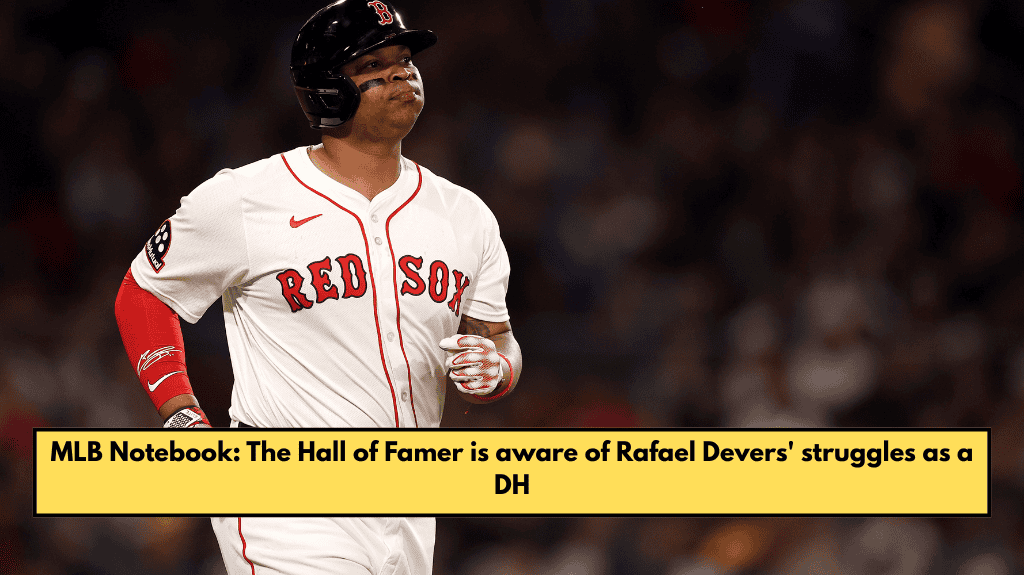

BOSTON — If anyone can relate to Rafael Devers’ transition, it is Edgar Martinez.

Martinez was promoted to full-time designated hitter after eight seasons as the Seattle Mariners’ third baseman. Martinez, like Devers, struggled defensively at third base. Like Devers, he wasn’t convinced it was a good career move.

It turned out to be the best thing Martinez could have hoped for. He went on to win two batting championships, four Silver Sluggers, and be named to six All-Star teams.

In 2019, his final year of eligibility, he was elected to the Hall of Fame. Not bad for a man who could “only” hit.

Martinez has observed the Devers transition from afar and understands the challenges better than most.

“For me, I struggled at first,” said Martinez, who is now the Mariners’ senior director of hitting strategy. “It was more about accepting that that was now my role.” At some point, I had to admit that the team was winning, we were playing well, and the team was better (with me as DH).

“Once I accepted and embraced it, I was able to move forward and establish a good routine that would help me excel in the role. But accepting it was the hardest part. You’re not sure where your career is going. What happens if I go a month or two without producing? I wasn’t on the field, so if I don’t contribute with a bat…?”

For Devers, job security is less important. He has nine years remaining on a guaranteed contract with the Red Sox worth more than $280 million. That contract may bring additional scrutiny if he fails to perform, but Devers does not have to worry about losing his roster spot or being released.

Martinez recalls that it took “a couple of months” to settle into the DH position. He needed to figure out a routine that worked for him and how to spend his time between at-bats.

“You have to have a routine with your training,” Martinez said, “because if you don’t move around much, you can easily get out of shape.” You must maintain a consistent routine throughout the day. For me, it began in the morning with how I prepared for the game, and it continued throughout batting practice and the game with my routine, which included hitting off the tee, hitting off the machine, riding the bike, and getting my legs ready.

“There was also a mental component, which involved anticipating situations during the game. Take note of the pitcher’s approach to our lineup and his attention to detail. All of this kept me interested in the game, so I wasn’t just sitting there thinking about my at-bats.”

Martinez pointed out a drawback of the role. It’s easy to focus on the most recent plate appearance and what went wrong, especially when a player is struggling. The key, he explained, was to pay attention and prepare for the next at-bat.

“For someone trying to hit,” he chuckled, “thinking too much is not a good thing.”

For much of Martinez’s career, players did not have access to iPads to study their most recent at-bats.

“I used some video,” he explained, “but when I was satisfied with my swing, I might just focus on the pitcher. We used to rely heavily on watching the pitcher (from the dugout) for each pitch.

Too much information is bad. You do not have the proper focus. Hitting a baseball should be simple: you see it, then hit it. And I discovered that taking a simple approach was when I performed best.

Even since Martinez’s election to the Hall of Fame, the position of DH has shifted dramatically. For decades, it was exclusive to the American League; however, in 2022, it became universal, with the National League also adopting it.

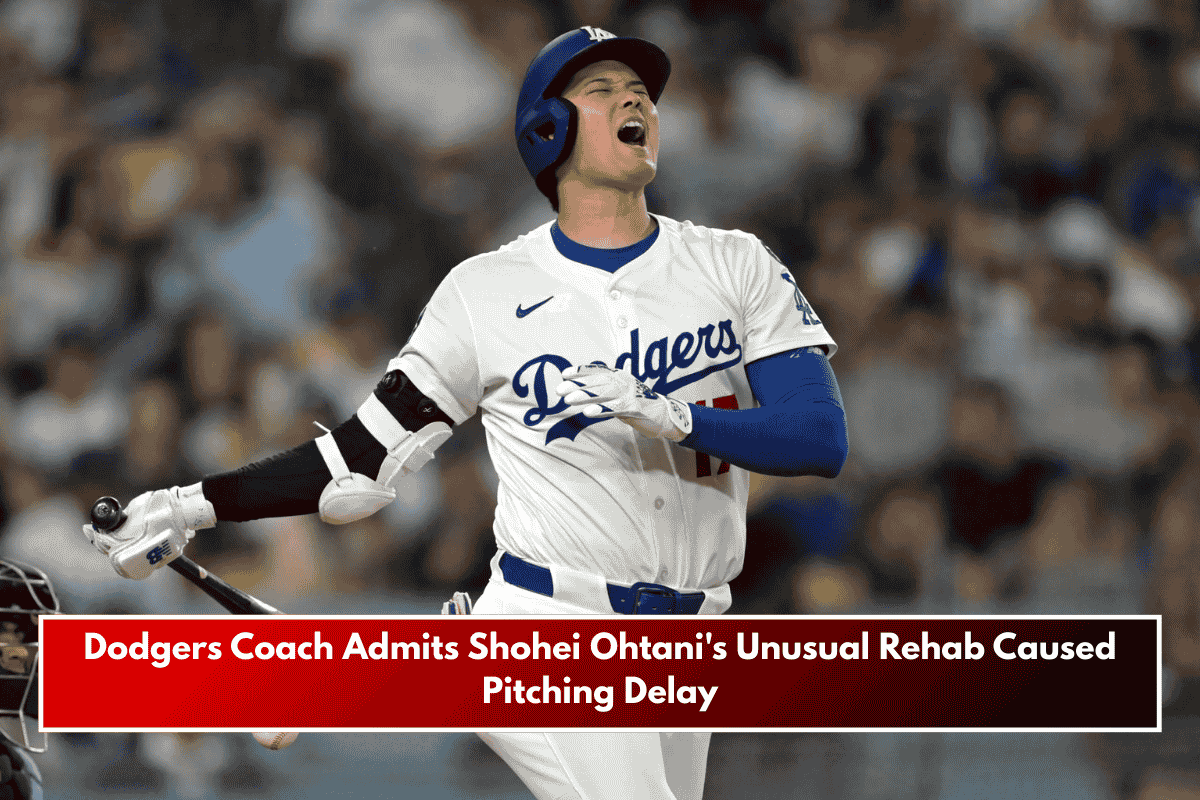

Major League Baseball has named the DH of the Year every year since 1973. In 2004, MLB renamed the award in Martinez’s honor. (Ironically, while Martinez won the award five times, Red Sox’s David Ortiz won it eight times. Shohei Ohtani has won it the last four years and appears to be on track to surpass Ortiz’s total by the time he retires.

However, in recent years, teams have begun to approach the role differently. While a few teams rely on an elite hitter almost every game—Ohtani, Houston’s Yordan Alvarez, the Yankees’ Giancarlo Stanton, and a few others—the majority prefer the flexibility of rotating players through the position.

With only four reserve position players on each roster, teams prefer the idea of prioritizing versatility.

“It’s not like it used to be,” Martinez admits. “Now, the DH could be used to give a guy a break (from playing defense), who has been playing every day. So, things have changed. I can’t think of many guys today who are (only) DH.

“It has evolved and changed. Will they return to the way things were? Who knows. However, it appears that the team is currently more concerned with having an extra player who can move around and play a variety of positions. Many teams now have two or three players who can play almost every position, which is becoming more important than having only one DH.”

Though they may prefer that approach—recall that, in the weeks following his hiring, chief baseball officer Craig Breslow stated that such a roster-building approach would be his preference—the Red Sox have chosen Devers.

And, as he struggles in his first month, the Red Sox can take comfort in the fact that one of the best to ever fill the role struggled as well.

The catcher’s position is about to change, possibly dramatically.

“From a 30,000-foot view,” said Jason Varitek, who started nearly 1,400 games behind the plate in his 15-year major league career, “someone who can move the baseball and catch the baseball may be less appreciated.”

Baseball has been experimenting with versions of ABS (Automated Ball-Strike System) in recent minor league seasons, as well as in major league spring training this year.

Initially, the minor leagues tested two versions: one that is completely automated, with balls and strikes determined by computer, and another in which the home plate umpire continues to call pitches, with teams able to challenge calls.

If the challenge system is implemented, the catcher’s role will not change significantly. They’ll continue to try to present — or “frame” — pitches as best they can, in the hopes of converting some borderline pitches into strikes by receiving — or subtly moving it — into the strike zone.

However, if the fully automated system takes over, no amount of elite framing will change what the computer perceives — a ball either crosses the plane of the plate within the strike zone or it does not, and no amount of catcher sleight of hand will change that.

“If it’s the challenge system, outside of the potential for challenges, (framing) will still be just as important,” said Varitek, the Red Sox’ game-planning coordinator. “You will still need to be able to control your strike zone. It depends on which way it goes. It’s difficult to give a definitive answer right now.

“Whatever it is, we’ll just have to operate under the rules and put our catchers in the best position to succeed.”

If the fully automated system is implemented, framing will become a devalued skill, while other aspects of the position, such as the ability to block pitches in the dirt or throw out baserunners, will become increasingly important.

Furthermore, the physicality of the catcher will change. If framing is unimportant, how a catcher’s body is positioned becomes less important. Catchers will crouch or squat for comfort and flexibility, regardless of how this will affect their ability to present pitches to the umpire.

As baseball becomes more reliant on data and analytics, certain aspects of the position cannot be quantified. How, for example, does a team rate a catcher’s ability to calm a pitcher in the middle of a jam? Or determine how to best use a pitcher’s repertoire during a given game?

“There’s not yet a measurement that we completely rely on,” Varitek told me. “We must rely on humans to make those decisions.

Another unintended consequence of installing the ABS system could be a tighter strike zone. In the minor leagues, the top of the current strike zone could not be properly measured, causing the zone to drop by about the size of a baseball.

“As a hitter, you can become a lot more selective,” Varitek said, echoing comments from minor league players and staff. “You’re not as worried about balls at the top of the zone.”

As Varitek reflects on his own career, in which he caught more games than any other catcher in franchise history, he is not disappointed that framing became a focus after he retired.

“Catching was hard for me,” he admitted. “What these guys can do is complicated. When I was playing, all I wanted to do was catch the ball. It has advanced significantly.”

No matter what system is implemented, the fundamentals of catching will not be overlooked.

“I think you always have to worry about the fundamentals,” he joked. “You need to protect 90 feet and keep the ball in front of you. And the one-knee (set-up) has helped; even though the eye test does not show it, there are far fewer wild pitches and passed balls. It may not appear that way, but there’s a lot more that got away with (catchers in the traditional crouch).”